MARCH 1999 by Ronda racha penrice

With titles such as Enter the 36th Chamber of Shaolin, Sweet Sweetback’s Badasssss Song, Black Spring Break, Soul in the Hole and Dolemite, the Xenon Entertainment Group caters to Black urban Hip-Hop audiences in ways that other distribution companies/major studios have not. Even with major players such a New Line Cinema entering the competitive and lucrative video market with feature film video titles like Players Club, Xenon still has a leg up on the competition.

Catering to tastes long ignored by mainstream studios, Xenon keeps its edge through a strong, albeit struggling, nationwide distribution network of mom-and-pop shops in addition to mainstream outlets such as Blockbuster Video, Musicland, and Sam Goody. Boasting hard-to-find Blaxpoitation titles like Black Godfather as well as an enviable catalog of kung fu titles ranging from the 5 Lady Venoms to the Hong Kong Specialist, Xenon has the young black market on lock–a very unlikely feat for a 41-year-old white guy from Seattle. But that is exactly what CEO/founder S. Leigh Savidge has accomplished.

“Xenon never set out to be a distributor of mostly black films,” says Savidge, who started the company 13 years ago in the general video market with $17,000, one title and a partner who lasted four months. Savidge stumbled into what he calls “the black niche market” by keeping his ears open to what consumers wanted. As the onetime standup comic struggled to find outlets for a comedy tape featuring himself and Jay Leno, mom-and-pop distribution outlets were telling him that black consumers were requesting “very specific black films that were not on video.” Savidge redirected his efforts and began acquiring some of those titles.

While black-themed film projects are more common these days on cable stations such as Showtime and HBO or on the big screen via movie studios like Fox and Universal, when Savidge ventured into the market that was far from the case.

“For years, we were unable to get loans from banks because they felt that this market was going nowhere,” reflects Savidge, whose company still relies on its own cash flow. As black culture continues to dominate the mainstream, mainly through Hip-Hop, Xenon continues to grow. In 1997, Xenon flexed its street savvy by releasing Thug Immortal, the Tupac documentary coproduced by writer Robert Marriott. Shipping at 250,000 units, a five-time increase over the typical 50,000, Thug Immortal spent an unprecedented 42 weeks on Billboard’s Top Video Sales Chart and helped propel Xenon’s 1997 revenue to $7 million, a record-setting amount for the company. Currently, a documentary about Death Row Records is in production.

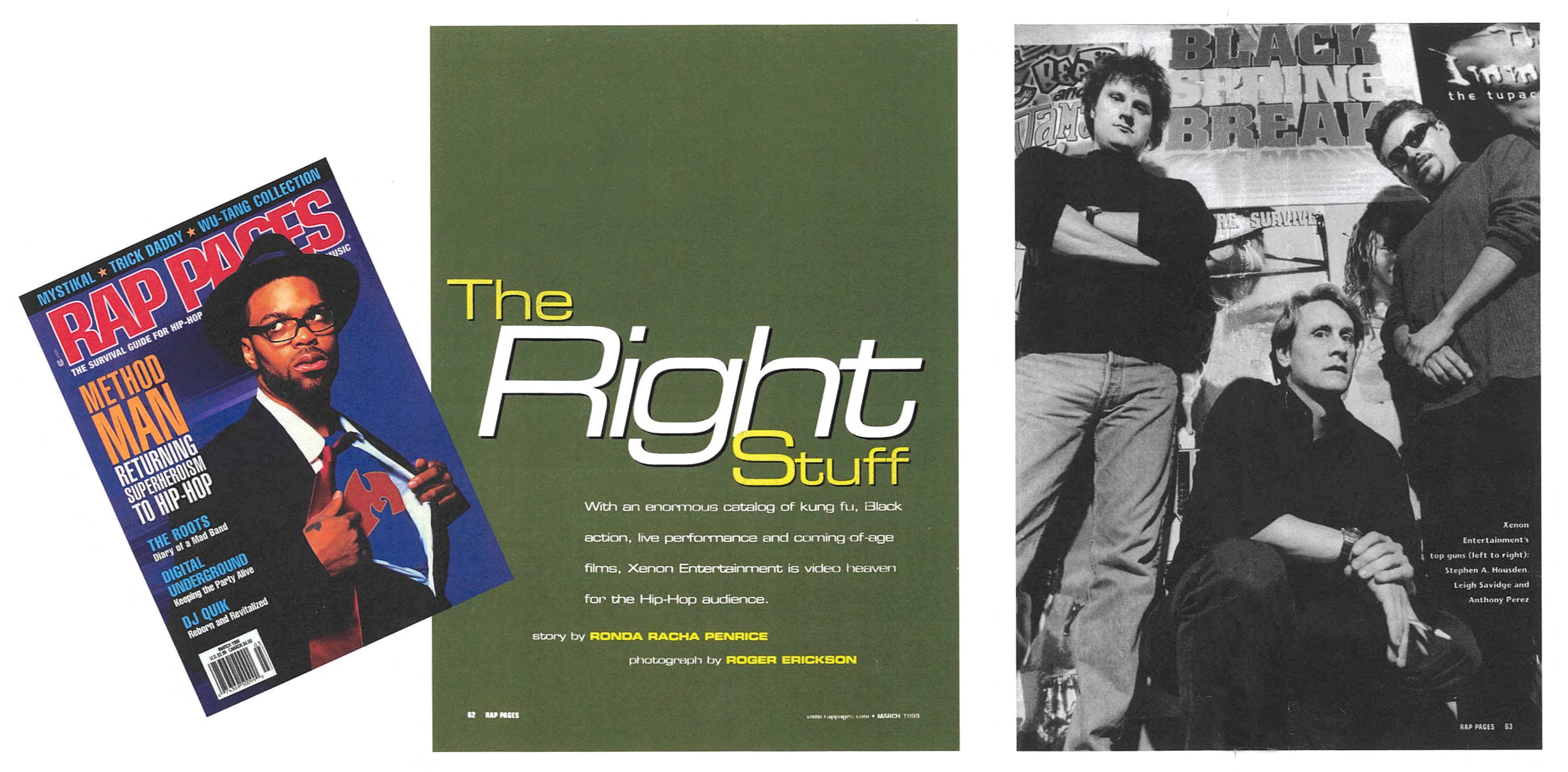

But Savidge credits Xenon’s success to more than good fortune. The addition of Stephen A. Housden, vice-president of acquisitions and production, and Anthony Perez, vice-president of sales and marketing, five years ago, according to Savidge, has been critical to Xenon’s increased popularity. And while the three meet and brainstorm daily, Long Beach native Perez, in particular, has helped Xenon target the urban audience more aggressively. It was Perez who met George Tan, Thug Immortals‘s coproducer and key advisor for Xenon’s kung fu collection, several years ago at a comic book convention and eventually won his trust.

In addition, Perez, whose passion, whose passion for comic books, rap music and kung fu flicks easily places him in the demographic Xenon actively targets, has helped the company capitalize on the undertapped Hip-Hop market by forging relationships with urban entities like RAP PAGES and members of the Wu-Tang clique such as LA the Darkman. But forging a relationship with Wu-Tang was inevitable. The group’s (and its various solo extensions) use of sound bites on the albums Enter The 36th Chamber, Tical, Only Built 4 Cuban Linx, Liquid Swords and Wu-Tang Forever from several unavailable Shaw Bros.-, Ocean Shores- and Dragon Video-produced films had already created a demand that somebody had to supply. So Xenon stepped to the plate and renamed some of its titles Enter the 36th Chamber of Shaolin and Ol’ Dirty Kung Fu and began offering them as Wu-Tang Collection, Wu-Tang Collection II and 36th Chamber Collection. Combine this success with the expansion of a kung fu cinema catalog already featuring Jackie Chan, Jet Li and Chow Yun Fat, plans for a record label on top of its acquisition of Hip-Hop video mag Color N.E.W.S. (an acronym for north, east, west, south), and Xenon appears to be sitting in the driver’s seat.

But, as Housden notes, Xenon’s diversification into martial arts and other areas is just about three years old. “Xenon entered the market,” Housden emphasizes, “appealing to a general black audience.” Black classic movie titles (Emporer Jones, starring Paul Robeson; The Bronze Venus, starring Lena Horn; and several films by 1940s filmmaker Spencer Williams) and gospel performance videos (the Clark Sisters, the Winans, Five Blind Boys, Commissioned and the legendary Mahalia Jackson) still make up a significant portion of Xenon’s catalogue. In addition, historical and sports documentaries like Huey P. Newton: Prelude to Revolution, the series Story of a People, Stride to Glory, and The Dream Team help bolster Xenon’s overall credibility with a general black audience.

According to Savidge, Xenon is interested in “an authentic black perspective.” But none of this, Savidge says, would be possible without the resurgence of black filmmaking. Spike Lee’s She’s Gotta Have It lit a spark that literally inspired a new generation of black filmmakers. Supporting Savidge’s observation, Housden says, “Black filmmakers have increased exponentially.” And even though Master P and others who have discovered you increased exponentially.” And even though Master P and others who have discovered you can do it yo’self are coming on strong, Xenon ain’t worried. Perez sees the success of people like Master P, whose independently produced I’m ‘Bout It shared top sales spots with Thug Immortal, as indicators of the viability of the market. “[I’m ‘Bout It] just reinforced the fact,” Perez says, “the market is hungry for entertainment that is catered toward them. They wanna see themselves up on the screen.”

Add the success of romantic breakthrough Love Jones, the film adaptation of Terry McMillan’s Waiting to Exhale and George Tillman’s Soul Food to the equation, and Xenon’s investment in the black niche market doesn’t appear to be a folly at all. The fact that Savidge is white, however, does bother some filmmakers enough not to work with him. “Generally,” says Savidge, who seems to understand their hang-ups, “a fair and honest deal wins them over.” Nonetheless, Housden still believes that “Xenon is in partnership with filmmakers,” especially as they make the giant leap toward developing, acquiring and selling films overseas, particularly with Africa and Asia.

Not straying from its roots, Xenon remains loyal to Blaxpoitation kings Melvin Van Peebles and Rudy Ray Moore. Peebles is a company shareholder, and Xenon and Rudy Ray Moore have several projects already in development. With census reports predicting sizeable black and Latino population increases as early as the year 2010 and the phenomenal success of “Wild Thing” rapper Tone Loc’s popular children’s series C-Bear and Jamal, Xenon ain’t loosening its grip any time soon.